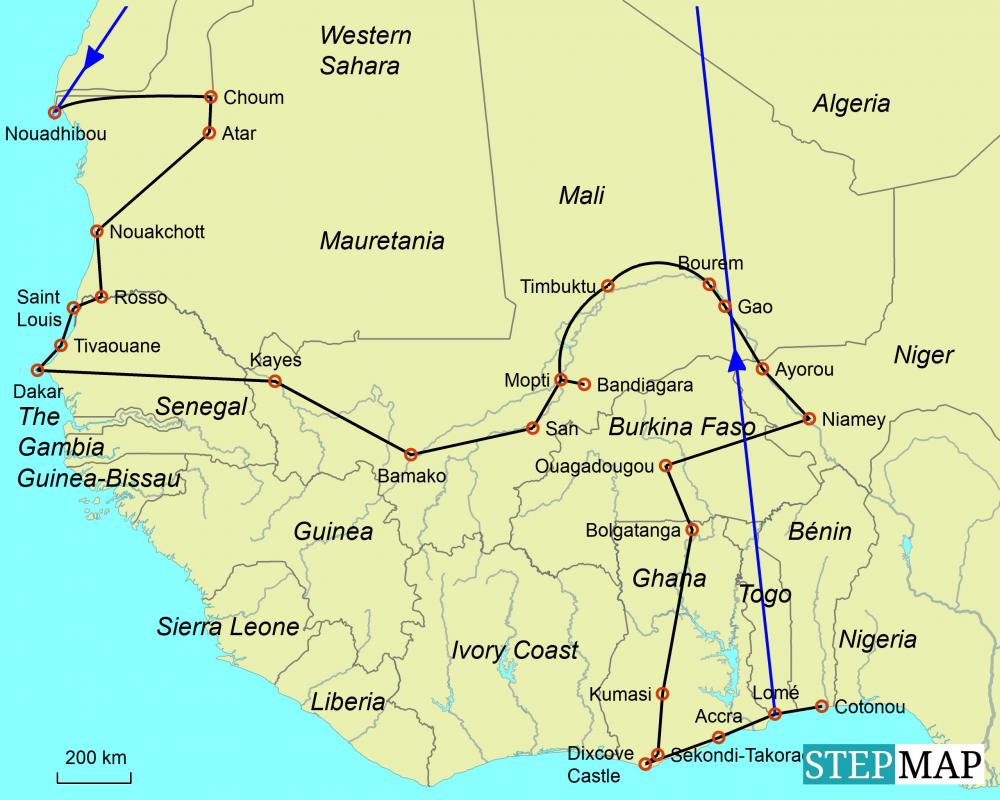

Mauretanien nach Benin [Historischer Reisebericht]

Von Mauretanien nach Benin

Individuelle Reise durch Westafrika 1978

Text und Bilder von Joachim von zur Gathen, Reisezeit 1978

Vor einigen Monaten hat Joachim der Redaktion eine knapp 800-seitige pdf-Datei zugesandt. Hier schildert er alle seine Reisen, die er in den zurückliegenden 50 Jahren unternommen hat. Diese Datei ist von Joachim eigentlich nur für den Privatgebrauch innerhalb seiner Verwandtschaft und im engeren Freundeskreis erstellt worden. Da ein Großteil seiner Familienangehörigen im Ausland leben und nicht Deutsch beherrschen, hat er seine Berichte in Englisch verfasst.

Joachim gestattet der Trotter-Redaktion Teile seines umfangreichen Berichts nun in dieser Sonderausgabe zu verwenden. Zu einer Zeit, in den 1970er Jahren, als viele Reiselustige in Richtung Osten (Afghanistan, Indien, Nepal) reisten, wie das auch in dieser Trotter-Ausgabe zu erkennen ist, reiste Joachim nach Süden, nach Westafrika. Die Redaktion hat sich entschieden, den Bericht in Englischen zu belassen.

Joachims Reiseroute damals: Mauretanien, Senegal, Mali, Niger, Obervolta, Ghana, Togo and Benin.

Mauretania

[…] I fly to Nouadhibou, Mauretania, and meet Dorothea in Bamako, Mali. Her workplace did not give her holidays for all the time, and I leave two weeks before her to Mauretania. My attempt to obtain a Mauretanian visa in Bonn fails. Dorothea and I ride on my motor bike like hell to get to the Ghanaian embassy on time: arrival 15.55, they close at 16.00. No visa, of course. But after talking a bit to the embassy secretary, we eventually get the visa. Rush to the embassy of Mali in Bonn. They close at 18.00, but after some gentle persuasion, we also obtain that visa. I send my passport by mail to the embassy of Mauretania in Paris, and about a month later, on 1 September, get it back – without visa.

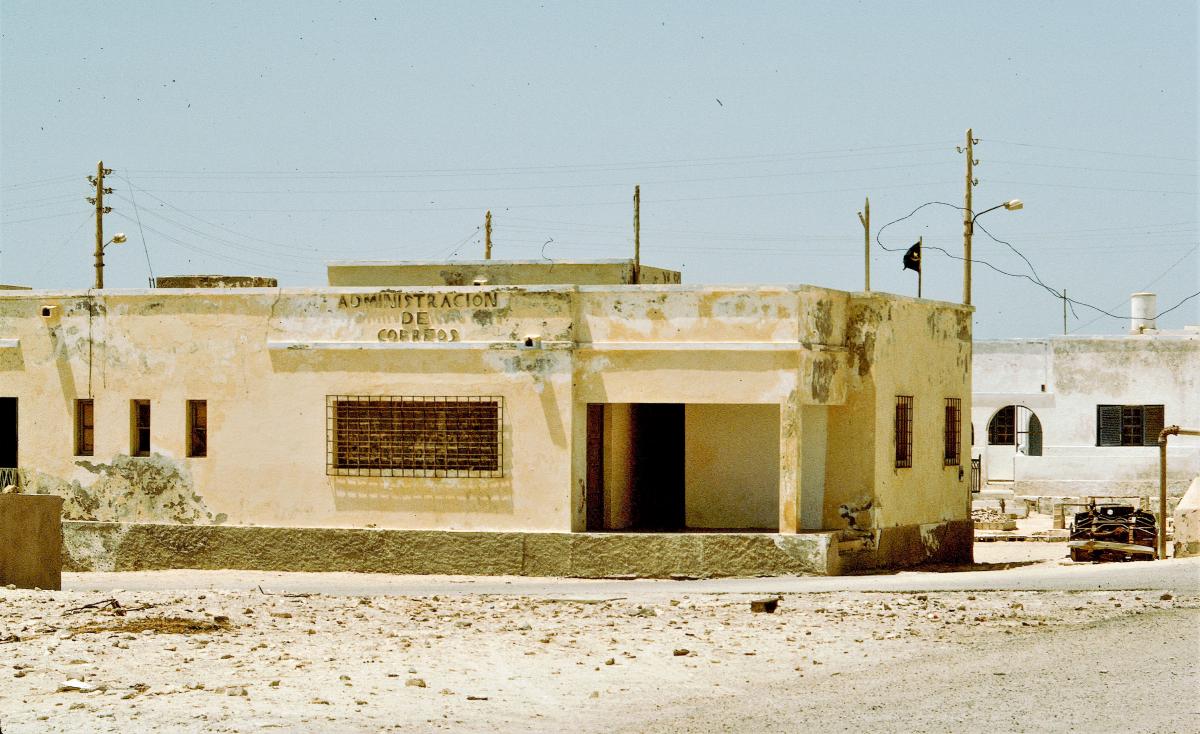

Nouadhibou center

I have already bought my ticket for 5 September. On 4 September, I take the early morning train from Zürich to Geneva and go to the Mauretanian consulate. I am extremely nervous, because if they also refuse, all our plans are void. And the ticket lost. They explain to me that in principle, they do not issue visas. Some sweet-talking, and everything goes quickly. I get the visa, am incredibly relieved to have the trip salvaged, rush back home to Zürich, get a train the next day to Paris. At the check-in counter there, my return ticket vanishes but later turns up at a different counter by miracle. And I am off to Nouadhibou. Rarely have I done a trip with that many initial obstacles. But then it turns out to be a wonderful and important voyage. My good luck is that I don’t believe in bad omens.

[…] Long queues wait at Nouadhibou immigration to Mauretania early in the morning. I fill my currency declaration rather non chalantly, because I do not feel like counting my treasures in front of so many prying eyes. Big mistake. At the next checkpoint, a soldier counts my money exactly and finds an amount of 5.000 CFA (Central African Francs, about 50 US$) that I had »forgotten«. Talking does not save me, he threatens to take me to his boss, and I realize that there is much more money that I forgot. So I cave in and let him keep his loot. I learned something, at a price.

There is only one hotel in town, quite expensive. Two guys take me to the Sweep Night Club. It is cheap, not too uncomfortable, with a lot of noise from the bar next door. After all the excitement in getting here, I sleep well. In the afternoon, I walk around the village, but there is not much to see. Nor is there much to eat in this place except some rice with fish sauce. Rather depressing.

The old Spanish post office in La Güera

It is a short walk into La Güera, once part of the Spanish colony of Western Sahara and ravaged in the long independence war. Most buildings show bullet scars or are demolished. A sad sight. 50 years ago, there was nothing here, just a runway on the Casablanca Dakar Line, used by Antoine de Saint-Exupery (1900-1944) of vol de nuit (and Le petit prince) fame, and some fishing. In 1978, and presumably still today, the »city« lives on the exportation of iron ore that comes from the rich mines 700 kilometers north-east in Zouérate and F’dérick. The longest train in the world, four locomotives pulling 220 cars with a weight of 17,000 tons and a length of three kilometers, brings the ore into Nouadhibou. It is emptied in an fascinating operation, where the complete train cars are turned upside down to empty their cargo onto conveyor belts. The ore then travels on freighters to all over the world, and the train goes back empty.

Besides a difficult 4×4 track along beaches, this train is the only land connection to the mainland. Everybody rides it, and so do I. With three friends whom I met at the station, we enter one of an endless row of ore wagons. These cars are quite high, and standing upright (not easy when the train is making its erratic way over the badly maintained tracks), you can barely look over the sides. The car is covered in red rusty dust from its load, and I come away with a deep red tan, but this washes off at the next occasion, five days later. It is a beautiful train ride through the night under a starry sky in an open freight wagon. Years later, they even added a passenger car to the train.

The truck at Choum

The next morning, the train slows down briefly without really stopping at Choum, a nondescript village. The tracks then make a sharp bend to the north and continue along the border with Western Sahara to the ore mines of Zouérate. At the »station«, all passengers, about a dozen of them, jump off the train. I throw my backpack over the wall of the car and climb out of the moving train. Quite some height. A heavily loaded decrepit truck is waiting to take passengers to Atar on the Adrar Plateau, via the Te-n-Zȃk-Pass. It carries bags, mainly of foodstuff, to more than capacity. The twenty or so passengers ride on top of this load, fresh air in the early morning, getting unbearably hot later in the day. The truck breaks down repeatedly, all passengers have to get off, and then we push the vehicle until the engine starts again. Atar lies at an elevation of 270 meters, Choum essentially at sea level.

After leaving the coastal plain, the truck chuggs and stomps along the steep bad dirt road, until once again the engine fails. This time, there is no chance to push it upwards. I ask the driver why he does not roll backwards in reverse, to engage the engine. The reason he gives is illuminating: the truck’s brakes do not work. So of course he cannot roll backwards. It gives me the shivers to think that I have been riding a heavy vehicle without brakes along a steep mountain road.

Worse is to come. Not far from the broken truck, there is a hut with people sitting in it. I ask to enter and am given a friendly reception and some fresh goat milk, still warm. But then some islamistic hot-head turns up and incites these hospitable people against me: »You are not a Muslim and do not deserve to be here.« Knifes come out. An ugly situation, worsened by the fact that they only speak Hassaniya, a local dialect, and we have to talk in broken Arabic from both sides, including quranic citations from myself. I remind them of their own rules of hospitality, and that I am also »a man of the book«, meaning Thora, Bible, and Quran, which is not quite as bad as just being a heathen. I can barely avert disaster and am happy to get out of this inhospitable place.

After hours of waiting, finally a pick-up truck takes me to Atar. I fall into my bed in a small guest house, completely exhausted physically and mentally. The place is depressing: no shade, no green, only sand and brown. Perhaps due to the exertion, I do not feel well the next day. It may be a heat stroke, not implausible after walking in the hot sun with over 40 degrees Celsius in the shade – if you find any. I lie down, drink a lot, but it is a miserable day.

After a long wait in Atar, the bus to Nouakchott, the capital of Mauretania, is not comfortable but a huge improvement over that hellish truck ride from Choum. We stay overnight in Akjoujt, a copper mining town. The wind keeps blowing sand in my eyes. But the next day, a sandstorm produces a complete white-out (rather a brown-out), 20 meters of visibility. Luckily, the driver is quite careful, different from other experiences in Africa.

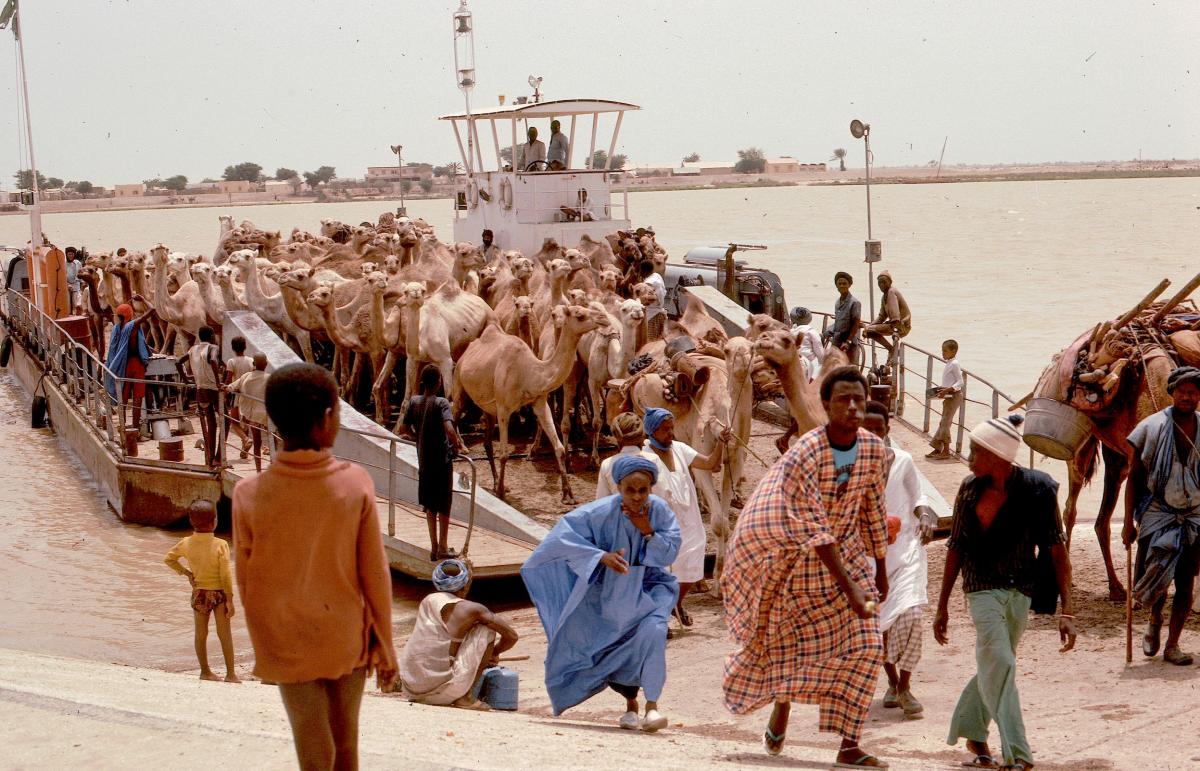

In Nouakchott, I can buy delicious apples and oranges to my big surprise, which completely cure my heat stroke. I take my first shower since Zürich, urgently needed. The sand has turned my hair into strands of concrete. I travel via Ksar to Rosso, the border village on the Senegal river. Children play in its light brown, slowly moving waters. The ferry to Senegal carries mainly camels, loud belching and bleating, the deck is thickly covered with camel dung. A wonderfully soft carpet. Strange border formalities. The Mauretanians note my name in a book, no stamp in my passport.

Ferry across the Senegal river in Mauretania

Senegal

On the Senegalese side around noon, the immigration boss is away drinking: »he’ll be back in a few hours«. Nobody knows exactly when. Well, thank you, Yours Truly is not inclined to wait for this incapable and incapacitated official nor will I be back in a few hours. So I enter Senegal without an entry stamp in my passport, a clever move that saves me from hours of waiting at the miserable immigration hut in Rosso and as a bonus procures me free accommodation for one night; see below. Yet another open pick-up truck takes me to Saint Louis, the famous fishing village on an island in the Senegal river. It is the oldest French colonial town in West Africa and was a base for Saint-Exupery’s postal airplanes. I stay in a rock-bottom hotel, a sweltering rathole with hardly enough space for my backpack. The rubber foam mattress has obviously seen a lot of action in its long life. My friend Vieux Badiane, a student despite his name, takes me to the military officers’ mess, where you can get drunk very cheaply. I do not, but stumble home for an early sleep after a long day. My sleeping bag protects me from the soiled mattress.

The next day, I take a long walk along the Langue de Barbarie, a stretch of sand about 100 meters wide and 25 kilometers long. On one side flows the river Senegal, on the other side is the Atlantic Ocean. Kids swim in the sea, some surf on wooden planks. The seamen’s cemetery is an impressive site. On hilly sandy terrain, rows of graves are decorated with a few wooden sticks and fishing gear, and fenced in with nets. An interesting tradition the like of which I have seen nowhere else, with the exception of a cemetery in Tonga decorated with empty beer bottles.

At 16.00 I take the train to Tivaouane, full of people, bags, cartons, chicken, and what have you. The local Wolof tribe has an amusing way of saying goodbye, a long dialog of tit for tat, obviously often funny, because the bystanders laugh a lot. They express agreement with an interesting clicking sound of their tongue. In Tivaouane, I am looking for some accommodation when a policeman stops me. He asks to see my passport, the only time in towns that this happened to me on this trip. Maybe they know about their lazy colleagues by the river. He leafs through it, then again, frowning, because he does not find my entry stamp. No surprise, since I have none.

I am arrested and escorted to the prefecture de police, a beautiful colonial building with white columns, a covered veranda, red tile roof and a large garden. This looks much better than any of the dumps called hotel where I have stayed so far. They take my passport away, but I am pleased when they tell me I am arrested for the night, saving me the hassle of looking for accommodation. Of course, you do not want to make this kind of booking for longer holidays. They allow me to take a shower and have dinner in a nearby restaurant. Georges Lamy, the friendly gardien de la paix, has taken out an old rusty iron bed for me. I throw some of the larger bugs into the fan that he has also provided – you can imagine the sound when the bug hits the fan. After that, a peaceful night under the stars, me smiling all the time at my luck in finding this fine accommodation.

The next morning, refreshed from an open-air night, I have my usual West African breakfast of café complet, a buttered baguette with Nescafé served in a tin can. The friendly policemen allow me to stroll through town. In one mosque, I join a band of kids climbing to the top of the minaret – marvellous view. Tivaouane is the capital of the Tijaniyya Sufi brotherhood and pilgrims flock to the tomb of leaders like El-Hadji Malick Sy.

Around 10.00, I go to the police station to pick up my passport and move on to Dakar. No problem until the commissaire arrives, a mean-spirited fat man. He mistreats his own people, and now revels at the opportunity of showing a foreigner his importance. An interrogation, aggressive from his side, then a telegram to Dakar: »The answer will be here by 12 noon«. Of course, that does not happen. My next stroll through town is in the close company of a plainclothes policeman. Eventually I can leave, but have to promise a visit to the Ministery of the Interior immediately on arrival in Dakar. Which I do – that is, the promise, but I have no intention whatsoever to spend a whole day in some dreary offices, possibly with ill-humored officials. My first action in my Dakar hotel is to scribble a fictitious Rosso, 11.9.78 into my passport. To my own surprise, that works … Pleasant stroll through the modern part of town, nice food and cold draft beer. Totally relaxed.

[…] Dorothea left yesterday evening from Paris to Bamako, and I take the train in the morning, also to Bamako. I am at the Dakar train station, a magnificent colonial building, early enough at 10.30, but learn that the seats were taken around 01.00. Tough luck. I travel 2e classe, place entiere, the luxury of a whole seat by myself, but sleeping is difficult on my narrow wooden seat. The train makes a long stop in Kayes. Several official arrival times in Bamako are provided, between Saturday, 16 September, 15.00, and Monday 06.00. That does not matter much, we cannot influence it anyways. With some Germans and an Englishman we have a few beers in the train’s bar, but the mood is somewhat downcast, nobody can really keep their eyes open for being so tired.

At 05.30, we arrive at the Senegal – Mali border. I am quite relaxed, what can they do to me because of my missing entry stamp? It works even better, in the morning twilight the immigration officer sees my hand-scribbled »entry stamp«, reads it out loud, nods, and gives me the exit stamp. Big relief! Finally Bamako, only three hours behind schedule. Right on time by African standards.

Dorothea and I have arranged to meet »at six o’clock in Africa«. Will she be there? Did she arrive in Bamako at all? Dorothea later tells me that everybody around was excited, waiting for some relatives to arrive. The platform is packed with people, she could not move or see anything and was shoved to and fro. And this for three hours. Then she discovers a bench on which she can stand with a view over the crowds. She falls down several times, but always lands on some people. The excitement grows as the train comes into sight. The train stops, people get off, an incredible din and chaos. But Dorothea has a strong voice and was the loudest to cheer and wave like crazy: »Jo … Jo … Jo!« And then she stands in front of me. We are both happy and relieved that I arrived at »six o’clock in Africa«.

The »elegant« bus station at Bamako does not contribute to Dorothea’s well-being

Mali – Together with Dorothea

We move from her moderately expensive Grand Hotel to the cheap Auberge de jeunesse (Youth Hostel). A grotty place, dirty, toilets almost unusable, rubber foam mattresses on the floor, plenty of mosquitos. Dorothea is mad, understandably so. Dorothea sleeps terribly badly because of the mozzies. The next morning, Dorothea is already angry in the dirty shower. I take her – not meaning any harm – to a cheap place in the street for café complet, as I had taken happily each morning in the last week. […] Not really relaxing, we take a taxi brousse (bush taxi) for 300 kilometers to San. A friendly passenger, Amada Sanyaré, in the car invites us to his home. A pleasant evening in the middle of nowhere. […]

Next morning, we stroll around the pleasant town of San, down to the Niger river, across the market, where many men are weaving tissue for cloth. Good-bye and a little present to Amada’s brother, who accompanies us all morning. Dorothea and I cram with ten others into a taxi brousse for Mopti, a robust Peugeot 504 station wagon that serves as bush taxi all over West Africa. Dorothea has a seat, but for me it is only standing room outside at the back of the car, very tiring and giving me a major muscle ache after this gruelling ten hour trip. We pass many check points and stop for food and other necessities. At midnight, we arrive in Mopti at a nice campement with mosquito nets for an excellent sleep.

The Great Mosque at Mopti

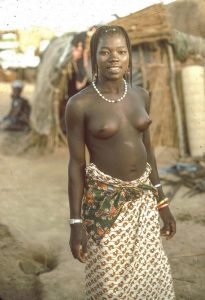

We spend several days exploring Mopti, a fishing town on the Niger river. Its Great Mosque (or Komoguel mosque) is a showpiece of West African adobe architecture, but it was actually built under French supervision in the 1930s and has a height of 15 meters. The heavy rains work hard on the façade, crowned by three towers. Hefty tree trunks protrude from the walls for use as ladders during the necessary repairs. Children are everywhere, often naked, loud and friendly, we have to shake hands all the time. Many women walk around with bare breasts, including young pretty girls.

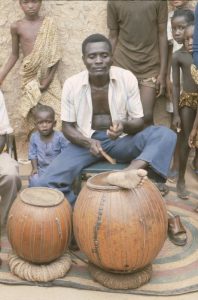

Dorothea gets invited into a courtyard, where the women show her how to crush millet for fufu, the main staple here. When she tries, her clumsy attempts meet with laughter. The pestle, made of heavy wood and about a meter tall, feels like weighing a ton and is difficult to move without experience. But then they show her how – wong, wong – easy this is, accompanied by singing and clapping hands. The millet flour is then mixed with (stale) water and saliva and left to ferment until it becomes a slurry and sticky mass, the fufu. We usually like the local food, but already the stench of fufu is enough to turn us off. And the taste matches the smell. We buy woollen blankets, rather scratchy, and a nice Dogon fertility statue.

Thrashing fufu

22 September is Independence Day, for us a big adventure with incredible sights. At 08.00, we are on the big square by the quay and get the last two seats on the tribune for special guests. Will we be able to stay here? With luck, we may. After a long boring speech by some official, a big and fascinating parade starts. A motley crew in uniform and with battered instruments has gathered, and they march proudly along, everyone applauding their cacophony. A wonderfully native spectacle. They all wear same-size shoes on their feet of rather varying sizes. The Mopti Cacophony Orchestra, staffed by the Malian armed forces. They remind us of the amateur bands called Guggemusig that parade through Zürich during Fasnacht (carnival), loving their own sound and oblivious of its effect on others.

A street photographer (left ) – A proud young woman (right)

[…] One of the high points is a boat race, with around 30 people per boat, the numbers vary and nobody minds this. They row on the opaque brown waters of the Niger river. Sweat is flowing, and the river water is so much laden with silt and decomposing organic matter that it resembles an elastic substance, like rowing in chewing gum. Their is no rhythm or rhyme to their rowing, just everybody pulling as hard as possible with a lot of energy. One of my photographs made it to the cover page of Schweizer Familie, a Swiss magazine for which I wrote several pieces on traveling at the time.

Festive atmosphere

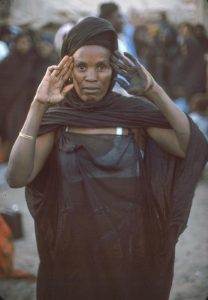

Proud women show off their treasure: massive golden ear ornaments (earrings is not the right word). They are too heavy for a hole in the ear and are fastened with a band looped around the top of their head. This constitutes their dowry, an insurance against financial hardship in case of divorce. It is easy for a husband to terminate a marriage, and he has no financial obligation to his ex-wife.Unmarried women flount simple jewellery and whatever else they have. In the afternoon and evening, the whole town is dancing in the streets, children, adults, Dogons in their traditional costumes or even on stilts. The exuberance is mesmerizing, such a happy day. Our ears are filled with the music (or noise) of tam-tams, drums, other instruments, acrobats, Dogonstilt-walkers, and dancers.

We take a taxi brousse towards the start of our long walk along the Bandiagara escarpment. It is a steep cliff where a high and a low plain meet, around 150 kilometers long and up to 500 metres high. This ridge of brown and purplish rocks and boulders is one of the most impressive landscapes in Africa!

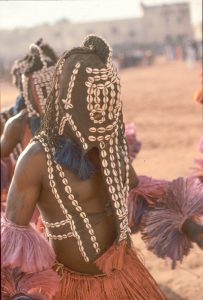

The peaceful and friendly Dogons live along the base of the escarpment. They have developed a rich culture, including huge masks that fetch high prices at art auctions and woollen headdresses decorated with shells. We have seen a group of them dancing on stilts during the Mopti festivity. They bury their dead in graves high up in the escarpment. The living share large palm-thatched rondavels, and millet is stored in small huts on stilts, in order to keep rodents out. Their vibrant culture still shapes their everyday life. I buy a marvellous piece of Dogon technology, a wooden lock to a storage hut, a traditional piece of cryptographic hardware. When you push the bolt to its closed position, nails tumble down through irregularly spaced holes from a higher level to keep the bolt in place. To open it, you insert a long rectangular wooden key with pins pointing upward that push up the locking nails – and in you are. But only with the correct key. Later the same year, I stayed at a hotel in the USA which employed a similar system, just with metal pins and a plastic card instead of the wooden key.

First we pay the compulsory visit to the chef du poste de police, very friendly and with stamps vu au passage in our passports. We get some fufu with peanut sauce in a tiny restaurant, just a mud hut inhabited by hundreds of flies. We can hardly get down the unappetizing food – but what else can we do? People are exceedingly welcoming.

Past Sassambourou we walk the whole afternoon in the hot sun, stopping at every rivulet for a rest and splashing us with water. Since we are carrying all our luggage, the hike is quite strenuous. Around 18.00 we find a nice creek and have our luxury dinner there: a whole can of pineapple from Côte d’Ivoire, claimed to contain ten tranches entires d’ananas, but there are only small pieces in the can. So what … such trifles cannot spoil our wonderful meal. We continue hiking in the dark, no moon yet. It is not always easy to find the trail and to avoid the puddles. Finally we settle down for the night in a flat spot. Swarms of mosquitos descend on us. Unfortunately, poor Dorothea’s pants end somewhat above her socks, and on those ten centimeters of flesh, she gets bitten by dozens of mosquitos. Scratch scratch. We do not carry a tent and just lie in our sleeping bags on the ground of hard mud, heads covered with a shirt against the ferocious creatures. It is a wonderful 1000-star hotel out there, under the open African sky, no-one within kilometers from us. Not for a minute do we worry about wild animals, snakes, scorpions – worrying would not make a difference in any case.

We wake up at sunrise. Extensive morning wash in a creek, delightful. This frequent washing and refreshing at flowing waters is one of the nice things on our hike. The village of Koron with its – sorry – dirty and smelly inhabitants confirms our impression that we chose a better place to sleep out in the open. The restaurateur des douanes Abdulaye Ouédraogo invites us to his guest hut, together with many children and flies. Nice café au lait, not so nice fufu and gȃteau au mil (millet cake) – in fact, we cannot get any of it down – and wonderful tomatoes, of which we buy a few for on the way.

From Koron we hike to the top edge of the escarpment, on a trail that is well visible through the fields, but on large rocks we see only faint traces of sand. And then comes the most exciting part: the descent down the escarpment, about 150 meters high at this point. A tiny cleft in the almost vertical walls provides a narrow and steep path, always with impressive views of the plain below. The only living creatures we see are birds nesting in holes in the walls. At the bottom, a refreshing spring waits for us. In a small village near Nombori we help a few people with our non-existing medical knowledge, barely enough to administer some Spasmo-Cibalgin and clean out some eyes. In Nombori, the village teacher invites us to his home. He does not speak a word of a language that we understand, and our Dogon So is equally poor. We do manage to understand that the large white holes high up the escarpment are their burial places. They can usually only be accessed by experts using ladders. Sleep does not come easily because of the mosquitos, although both of us are dead tired.

Breakfast is a can of Nescafé for both of us. It takes some time to cut the wood, light the fire, boil the water, and pour it into a tin can. […] Walking through sand, millet fields, swamps, and small rivers, we chance upon another pleasant creek for a long refreshing break. Everywhere we meet friendly people who rarely see white foreigners. Later we hear a lot of noise from the distance, and on getting closer, we see that we are arriving at the market in Tirelli. Everybody is getting drunk on millet beer, the best thing they make of millet.

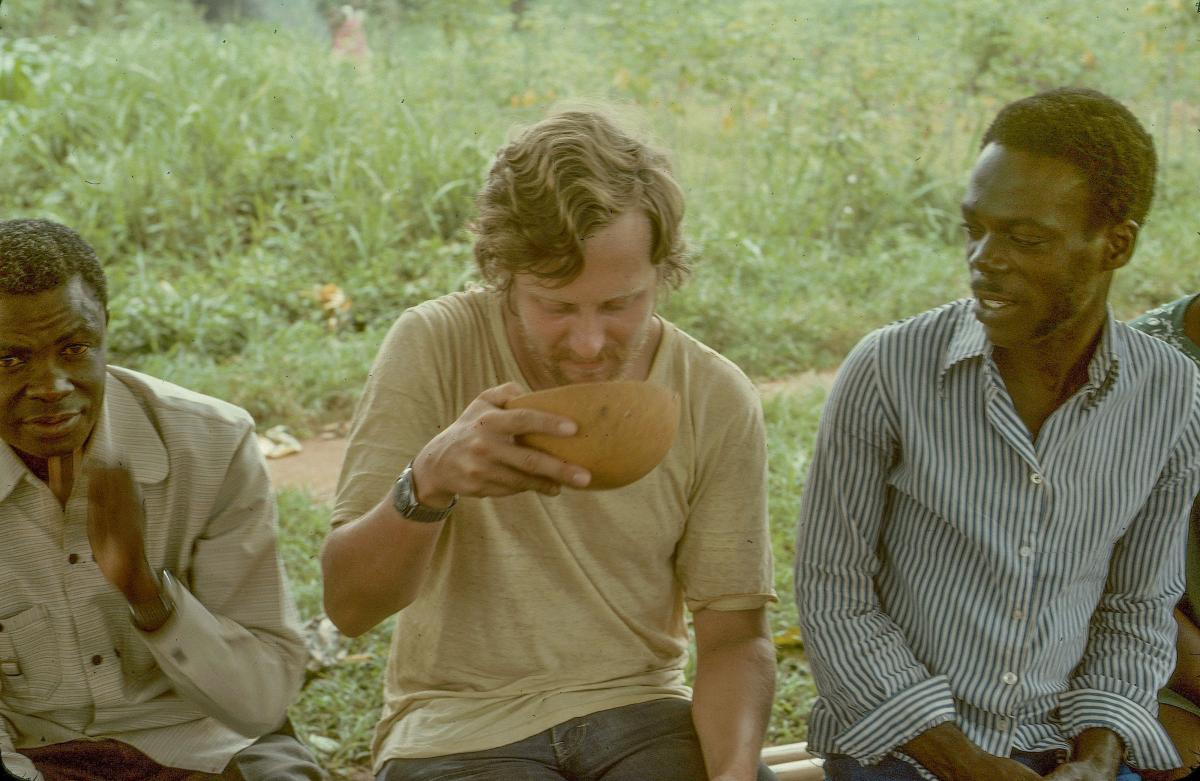

We have pretty much adapted to African standards of hygiene and share with everyone beer from one of the large calabashes. This is quite a potent drink, I have a bit more than Dorothea, with a sorry result. On leaving, I lead the way as usual, but this time in a completely wrong direction, intoxication plus midday heat working hard against my brain. And successfully. My more sober companion Dorothea and some locals correct me several times, and we retrace our steps. At least I can still walk …

We arrive just before darkness at the village of Amani. Without even asking, we are pretty soon invited into a hut, sit on the guest mat, and are served water, inedible (for us) millet stew, nice chicken and tomatoes. Our »mattress« for the night is a layer of reeds on a solid ledge of mud. When we wake up, we look at each other with surprise: both of us have long strips of indentations running along the whole body, most markedly in the face. Then we understand: these impressions come from the reeds on which we have slept. For the start of the last day of our hike, our host accompanies us a while, saving us many detours. Finally the steep climb up the escarpment, a painful enterprise with our luggage. At one place, rocks are piled up on each other in a dramatic way, and you have a wonderful view of the valley below. A relief is waiting for us: a local man is willing to carry our luggage up the rest of the way. In the village of Sanga, civilization hits us again: orange juice at outrageous prices, but we do not mind at that moment. We get an expensive lift in a car to Bandiagara. It starts raining really hard, within minutes everything is inundated, and we are driving through fast creeks. Luckily this has not happened on our trek. We have our first real dinner since a few days, and even find some cold beer. And we have a whole night before us, on a real mattress and without mosquitos. What a luxury! […]

On the Niger River

Timbuktu

Ever since our 1973 desert outing in Morocco, I have dreamed of traveling to Timbuktu, even if not in »52 days« by camel caravan. […] In Mopti, we board right away the ferry Général A. Soumaré of the Compagnie Malienne de Navigation to Timbuktu. Some annoyances by the ship’s aggressive staff end with Dorothea slapping a big fat steward right in the face. Eventually we settle down peacefully outside on the Second Class deck with our Fourth Class tickets, spreading our sleeping bags and the recently purchased blankets in a comfy corner.

The big river adventure can start. The ship is completely full, people have put long planks across the railing so that they can sit on their end, high above the water. A scary sight, reminding me of teeter-totters in my childhood: if everyone at the low end gets off, the others take a big splash. But they do not do us the favor of playing this silly game. The boat stops at numerous villages along the river. There are no quays to bring the boat close to shore, so she anchors in the river and departing passengers have to take a long swim through the muddy waters. Graceful vendors swim out to the boat, offer food and even milk from calabashes that they balance on their heads, in the water up to their necks. In shoulder-deep water! It takes some agility to balance a bowl with chicken on your head while you swim quite a distance.

The first part of the river voyage is through the semi-arid Sahel zone in which we have spent many days, with millet fields reaching down to the river banks. Getting north, the landscape turns drier and drier, and finally gives way to real desert, with nothing but sand and dunes visible. Timbuktu was originally connected by a canal to the Niger river, but that silted up a long time ago, and its present port is Kabara. On this trip in 1978, even the canal from the main river bed to Kabara is impassable for our Général, and we transfer into a pirogue that can handle the shallow canal. Then a bush taxi for the 18 kilometers into my dream town. What a place! Sand, sand, sand everywhere, including our eyes and mouth. After the compulsory visit to the police and declining several offers of camel rides and trinkets, we eventually arrive at the campement. A beautiful old stone construction, walls completely around it, large round-arch portals, and a pretty courtyard in the center. The old wooden doors are adorned with typical Tuareg metal ornaments. And then, finally – a cold drink and a shower. In the afternoon, a Tuareg tea ceremony and a beautiful sunset over the desert.

Main street in Timbuktu

Cold beer is available in the new Yugoslav-run supermarket, which fits here like a UFO landed in the desert. But mainly we enjoy wandering around a true desert city. Daytime temperatures rarely drop below 40 degrees Ceslius. Apparently, some madrassas (schools, universities) and mosques hold rich collections of old codices, manuscripts written many centuries ago. We do not have access to such things, people are rather closed towards us foreigners.

In 2012, Islamist Tuareg rebels took the city. They eventually fled from the French and Malian military, not without setting an important library with old manuscripts on fire. Today, it is not advised to travel into this area.

Our last leg in Mali takes us through the desert along the Niger river to Gao for 430 kilometers, and then to Niamey in Niger. There is little transport along this route. Eventually, we find a battered old truck going our way.

We are comfortably installed in the back of the truck, the sun beating down on us, sitting on bags of millet, leaning against the rear end of the driver’s cabin, together with an old rusty bedstead and other junk, two goats that balance precariously on this shaky voyage and pee all over the place, and a fresh leg of lamb hanging right behind us and getting all sandy. Presumably this heightens the haut gôut. On the dirt road, we get shaken and rolled like crazy, it is hard to hold on to anything. At some bumps, it feels like we were flying a meter high. Certainly better than a roller-coaster at a fair, and much cheaper for three days of this pleasure. It is hot, we are tired, and then Dorothea complains that something is hitting her arm all the time. She is too tired to even look, so I tell her to move a bit aside, away from the lamb shank that is molesting her. She does, all is quiet, we are used to this kind of thing. The road is all sand, with endless desert on the left hand side and the idea of the river on the right hand one, but we are too far away to see it. […]

The only relief are the frequent stops when the truck gets stuck in the sand. In the evening, we stop at a Tuareg camp and buy some fresh cow milk, still warm. We hope that this was it for the day, but the truck drives on until 03.00, like a Flying Dutchman. No thought of sleep, because every few minutes we are flying high in the air, then back hard with our bums on the millet bags.

The next morning, we witness a rarity: a rainstorm in the desert. It pours down. We find an old tarp that is normally used to keep away the dirt. It is hard to hold it up, and we soon have black rivulets of dirty water running down our arms and into our clothes. By now, this hardly bothers us. Finally, a coffee on the market in Bourem.

Dorothea relaxing on millet bags, lamb shank behind her and goat in front

Niger

In the late afternoon, we find a taxi brousse to Niamey in Niger. Mouraou Adama, the unfriendly driver, refuses to pick our luggage up at the hotel, and we have to lug it all the way to the taxi station. Leaving at 19.00, we have to stop frequently for repairs. They do not carry any tools or spare parts. Final breakdown at 21.00, after less than an hour of driving time. The car is only two months old. It is quite a feat of M. Adama to ruin this, normally very reliable, Peugeot 504, in such a short period. Clearly, it would not arrive in Niamey any time soon. Nor would we …

At 02.00 the next day, a truck picks us up to Ansago. It is also our hotel for the night, sleeping on bags of dates. Very early in the morning we put up camp under a tree in the village center. Nothing decent to eat or drink. We wait in the heat until in the afternoon, a car is going to Ayorou in Niger tout de suite. Meaning: in a few hours. After twenty minutes of driving, the engine overheats. Our prospects fall, but eventually they resurrect the car, and we cross the border from Mali into Niger.

After our exhausting desert trip from Timbuktu, we finally arrive in Ayorou in Niger and are looking forward to a comfy hotel. That is not to be, the only hotel is closed. We put our sleeping bags smack in the central square of the little town, cover our meager belongings with our blankets, and are rather worried about what could happen at night. After all, this is not the open country where only animals roam, mainly mosquitos, but a town where human animals might roam. Nothing happens, fortunately. For Dorothea, going to the toilet was a nightmare. It is less than comfortable, but the value/price ratio was ok.

There is nothing inviting to stop us here, and off we are next morning on a bus to Niamey, the capital of Niger. Each of us has a seat, a luxury we have not enjoyed for many days of tough traveling through the desert. On arrival at 17.30 in Niamey, an even higher level of luxury is waiting for us: a room in the pleasant hotel Moustache of Abdou Sidikou dit Moustache with a shower and a toilet, even with toilet paper. Wow! How modest our expectations have become! We are truly and totally exhausted after this strenuous trip, incredibly uncomfortable, little to eat or drink, and with the continual uncertainty of whether we would arrive or not. A night in the paradise of a bed, without rattling, shaking, flying through the air, hard metal edges against shoulder or stomach, and then a day of rest are highly deserved.

We stroll through Niamey, a sleepy town. The Grand Marché and the Petit Marché are interesting, but we are too tired to become active purchasers. The museum shows local villages and a dinosaur skeleton, but its most fascinating exhibit is the skeleton of the famous arbre du Ténéré. This acacia was the only tree within 400 kilometers in the huge emptiness of the Ténéré desert, even shown as a landmark on the usual Michelin maps. And then some idiotic truck driver ran into it in 1973, with fatal results for the tree.

Imagine: 400 kilometers on either side to pass, and still not to manage!

Upper Volta

One day’s rest is enough to get us back into shape, and the next day we want to go from Niamey to Ouagadougou, the capital of Upper Volta. We find a car that is leaving immediately. After seven hours of waiting, it does indeed start. In a sense, at least, since the starter is broken and we have to push it. This is, of course, frequently repeated. At each of the many police checkpoints throughout the night drive, all passengers have to descend, stand in line like a bunch of soldiers, and have their documents inspected by tough-looking but not very bright policemen. At one point, I give him my passport upside down, he leafs thoughtfully through it, nods, and hands it back exasperated to me, still upside down. But he wears a gun, so what am I to say? At these checkpoints, they always ask for money. We never pay anything and get with it. At one point away, Dorothea that she storms into the soldiers’ hut and shouts to leave us poor passengers sleep in peace – that helps, but only at that one checkpoint. Each time there is a scramble for the seats in the pick up truck with two long benches facing each other.

Normally these are tiring but uneventful drives. But on this one, the passenger next to us tries to pick a fight. We do not know what irks him. This troublemaker picks a fight for more space, shoving his elbow into Dorothea’s face. She asks him politely to behave properly, but he will not listen. We switch places, but he starts his elbowing game again, this time with me. I see a bend ahead in the road, take his arm, and throw him forcefully acrossthe aisle into the people on the opposite bench, aided by the centrifugal forces. Big applause for me from everybody – except the aggressor –; they all disapprove of his obnoxious behavior. The taxi stops, the others explain the situation, and the troublemaker continues his trip sitting on the floor of the car.

Lunch stop on the road

After some hours of sleep somewhere on the way, the driver continues the next day practicing for the Dakar ralley, racing at an incredible speed over the red laterite mud road, taking aim at every pothole, the deeper the better. At noon, in Fada N’Gourma, the car has to be repaired. I ask him politely, and with the nodding agreement of the other passengers, to drive a bit more reasonably. This earns just a snort from him. And then it happens. He hits a donkey, the car is stopped. True to his mentality, the driver does not apologize or offer any compensation to the poor peasant owner of the donkey, but scolds him (and the donkey) for having damaged his bus. As if the donkey had been driving at Fast and Furious speeds. He even wants its owner to pay for the damage to the car, while it was all the driver’s fault. A sad incident, and we do not know what became of the donkey, because we take off at breakneck speed right away.

We are so relieved to arrive in Ouagadougou (colloquially: Ouaga) alive. The main reason we are here is that I love this name, so melodic, so soft, such a pleasing sound. Besides its lovely name, the town does not have much to boast. Truckloads of mopeds have arrived recently, and they are being assembled everywhere in the streets. Oh well, we have traded loud mopeds for the wonderful silence at the Bandiagara escarpment. Such is life.

Ghana – »Traveling is you white man work«

We spend three slow days in Ouaga, running around for passport stamps and papers at the BNST (Bureau National de Securit’e du Territoire), but mainly enjoying good food and drink, some friendly people (and ignoring the others), and buying souvenirs. From Ouaga, we take a taxi brousse to Bolgatanga in Ghana. We chat with James Adoguya, a pleasant bus conductor working for the Omnibus Services Authority and carrying a bicycle. We correspond afterwards, I send him photographs and he sends me one of him with his wife. In his letter from November 1978, he notes that »Traveling is you white men work«. This acute observation hits right home: the locals see white people only traveling, and think that is what we do all our lives. If only it were so! Moreover, this bus-driving philosopher has inadvertently hit at the etymological connection between travel and work, travail in French.

Bolgatanga (Ghana) – Bus with »active« goats on top

At the Bolgatanga bus station, big women, all with a child strung on their backs, sell goods. Dorothea buys a beautiful straw basket. Afterwards, we wait in the bus to Kumasi for it to leave. Out of my customary politeness (haha, would Dorothea say), I have left the seat by the open window to her, and she leans out of the bus into the fresh air. Suddenly, she looks up to the clear blue sky and shouts »Look, it’s raining«. Ahem, I say, sorry, but I think we have goats on the roof of the bus. She dries her forehead and arms and that was it. This is Africa. You have to love it or leave it. […]

Steam loco at Kumasi

We take a bush taxi to Cape Coast, through dense tropical rain forest. What a visual relief after weeks in the desert and the Sahel! In our hotel, we meet Comfort, a women who spent five years in Germany with her husband, now divorced. Her comment: »Ghanaian men are all pigs. As soon as they have a bit of money, they only think of buying other women.« We visit Cape Coast Castle and Fort Williams.

Togo and Bénin

[…] After arriving in Lomé, Togo, we search for a nice place to stay, but end up in the lousy Hôtel de la Plage on the major intersection where the international road from Ghana crosses the main city thoroughfare. All night long, we are victims of the infernal noise of trucks stopping at the red light, then accelerating to get away. We stayed at noisy places elsewhere, but this probably takes the top of the decibel rating. Hot water shower on arrival, the only hot water the hotel has during our visit. We take a nice walk on the beach.

Some time before this trip, our friend Wolfgang Kory provided one of our motivations for this visit: he showed us an interesting ticket for a fine that had been imposed on him right here, pour chier à la plage. I would love to get such a ticket, but my digestion does not play along.

I go on my own to Cotonou in Bénin (formerly Dahomey), and Calavi. Dorothea does not feel like coming along. The country is rather different from its neighbor Togo. Revolutionary slogans are everywhere in the République Populaire du Bénin, large posters and pictures with slogans of socialism and international solidarity. I take an interesting boat excursion on the Lagune de Ganvié. A long time ago, the inhabitants of the shore fled into this shallow lagoon from warring invaders. It is 10 to 100 centimeters deep, and the dwellings are built on stilts, as in Lake Inle in Burma. The boat manoeuvres through gardens of water plants and tree trunks that are meant to attract fish. This lacustrine village has about 20.000 inhabitants who live from fishing. A peaceful (except for the noise of the outboard engine) and fascinating visit to people living on water.

On 26 October 1978 we depart back home. Dorothea writes her last lines in our diary, imitating the usual lengthy African greetings: »Ça va? Oui, ça va très bien. Adieu Afrique, bonjour Europe, le paradis nous attend. Tout parfait, les voitures parfaites, les restaurants pleins de boissons et avec d’énormes quantités de choses à manger. Qu’est-ce que vous désirez? Il y a de tout ce que vous désirez. Ça va madame? Ça va monsieur? Oui, ça va! Quelle chance pour nous d’avoir la possibilité de vivre dans le paradis!«

© Joachim von zur Gathen

Unterwegs-Sein

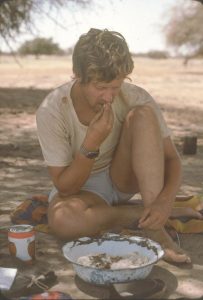

Joachim 1978

Joachim (Jahrgang 1950) ist seit seiner Jugend vom Reisefieber befallen. Wenn der Schmerz zu groß wird, gibt es nur eine Therapie: Aufbruch in ferne Kontinente. Auch wenn keine Krankenkasse das bezahlt.

17 Jahr, blondes Haar, damit fängt es an: sechs Wochen in Mittelamerika. Heute einfach, damals eine große Sache. Dann kommen größere Unternehmungen: mit dem VW-Bus von Zürich nach Kathmandu auf dem Hippie Trail, mit Frau und zwei kleinen Töchtern Transsib nach China und Japan, mit ihnen im Auto von Kanada nach Feuerland. Später Motorradtouren nach China und zurück auf der Seidenstraße, um den cono sur in Südamerika.

Inzwischen war er – als einer der wenigen dzg-ler – in allen UN-Ländern. Manche Freunde sagen, er war »überall«. Das stimmt natürlich nicht, es gibt in zehn Kilometern Entfernung von der Wohnung Orte, die man nicht kennt. Eine Reiseroute ist im Wesentlichen eindimensional, die Oberfläche der Erde aber zweidimensional. Aber wahres Reisen ist vieldimensional, es gibt ja nicht nur die Wege und Orte, sondern vor allem die Menschen, ihre Kultur und Gewohnheiten – von denen man manches lernen kann. Sprachkenntnisse sind dabei von Nutzen. Die vielen Freundschaften unterwegs sind bleibende Erinnerungen.

Nach Studium und Promotion in Zürich war Joachim Professor für Mathematik und Informatik in Toronto, Paderborn und Bonn. Seine Emailadresse von Januar 1981 funktioniert heute noch und ist womöglich die älteste in Deutschland. Weil mathematische Grundlagenforschung vor allem im Kopf stattfindet, hat er auf langen Reisen schon home office (oder road office) gemacht, bevor es das Wort überhaupt gab.

Auch nach seiner Emeritierung ist er aktiv in der Forschung und schreibt gleichzeitig seine Reiseerinnerungen auf. Der vorliegende Artikel ist ein kleiner Ausschnitt daraus. Viele Freunde und Verwandte haben das immer wieder vorgeschlagen, wenn bei einem Glas Wein solche Geschichten auf den Tisch kamen. Im Foto von 2019 zeigt Joachim genau auf die Spitze des Mount Everest (Qomolangma). Er ist seit den späten 1970er Jahren dzg-Mitglied.